From the Studio - Interview with Ian Friend | 10.12.21

In anticipation of Ian Friend’s first solo exhibition The Days Run Away, the JMG team recently visited Ian’s studio to learn more about his artistic practice. This survey exhibition features works from his earlier practice, as well as very recent creations including a series of sculptures, the first made by Ian in decades. Rather than provide a clear narrative for its audience, The Days Run Away invites the viewer to take pleasure in the abstract and poetic nature of its works.

In this interview, Ian joins Gallery Assistant Zali Matthews in conversation about his practice and the parcels of history, music and poetry that have inspired it…

Zali Matthews (ZM): Hi Ian, thank you for having us in your studio today. We are very excited to be showing your work at Jan Manton Gallery in early 2022, and are glad to have this sneak peek at a few of your works beforehand. Can I ask what your inspiration was behind this particular selection of works you are including in this exhibition?

Ian Friend (IF): Since this is the first exhibition I’ll be having with the gallery in its new space at Teneriffe, I’ve decided to focus the exhibition on looking back at previous works of mine. This will involve works covering twenty years. It’s an overview of my practice, and it’s going to be quite selective. I also think it will cover a few different approaches, all relating largely to poetry and to music, as well as issues of memory and imagined memory.

ZM: So, this will be a survey exhibition?

IF: A mini survey, yes. It will probably include about ten works, from quite small to large sizes. I would like to explore the idea that a small work can be as assertive in the same space as a bigger work, and that it’s just as important. I also hope that this exhibition shows consistency, and ongoing integrity.

ZM: Looking at your broader practice, it certainly seems like you stay consistent in your process of making and line of inquiry. I imagine that this will be quite a consolidated exhibition.

IF: I think so. Sometimes when I finish a body of work I do worry what comes next. At other times one seems to segue from one body of work to another fairly effortlessly. I think the best works are the ones that manifest their own life, and one is the agent in helping it come into being. Stravinsky comes to mind in relation to this when he said he was the conduit through which The Rite of Spring passed. It’s not quite like that as far as I’m concerned. We all make decisions about how things are going to look. You have choice about what you want to do. Even choosing the type of paper I use is instrumental in determining how the finished work appears.

ZM: Do you think that the materials used in your works form a vital part of the making process, then?

IF: Yes. I use materials which are fluid and often quite graphic as well. There are certain elements of chance that come into play when you're working with fluid media like gouache or ink; and then considered placement when you impose some graphic elements. When those fluid and graphic elements synchronise, you stop. The best feeling is when you look at a work and feel some distance from it. It stands on its own. I don't have to nursemaid it by having to explain.

One of the things that I'm conscious of is of there not being a narrative. Narratives are for novels. I don't like art that tells stories. I’ve just been re-reading Susan Sontag's “Against Interpretation”, which she wrote in 1964. It is still impressive. It's so strong in its assertion that a work of art doesn't need to carry some sort of narrative device, or any other reason for being other than it is.

ZM: You have previously mentioned that you often take inspiration from poetry, history and music during your creative process. How does that kind of content incorporate itself into your works?

IF: The titles of my works often refer to a specific poet or piece of text. But these references work in a very tangential way and develop over a period of time. It’s important to avoid being literal as this just leads to illustration. I learnt that lesson years ago, when I was trying to make some work that responded to T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets (1936-1942). It didn’t work at all, because it was too literal. It looked like an illustration. I even got in touch with Valerie Eliot, the poet’s widow, who told me that Eliot specifically didn’t want any of his texts to have images. He was correct. I destroyed those works in the end. I tend to make works in groups of three and five. And there is quite a high attrition rate in terms of destroying works.

ZM: Why in threes and fives?

IF: I don't like even numbers. It’s a preference I have. Once you set up one work, there's a focal point; with two, they're bouncing off each other. If you've got a triangle, you've got a three-part relationship. Four becomes two pairs. Once you get to five, you're in another zone. Five is a number that I like.

ZM: I understand what you mean. Even numbers seem too perfect – the conversation between them is too confined. With odd numbers, the conversation spills out.

IF: Yes, it opens up.

ZM: Can you give some examples of pieces of music, poetry or writing that inspired you while creating the works which have been selected for this exhibition?

IF: I don’t know if there are any specific references in these works. But the poet J. H. Prynne has been quite influential. He would be in his mid-eighties now, and he still lives at Cambridge. We have corresponded but never met. His work has stayed with me for forty years. The second example would be seventeenth-century Holland and the development of scientific enquiry counteracting church doctrine, principally through the endeavours of Baruch Spinoza. Johannes Vermeer painted two works, The Astronomer (c. 1668) and The Geographer (1668-69), both of which depict the same man, who is probably Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, one of the main developers of sophisticated lenses.

What I love about this is that there’s a duality about going into the microscopic and focusing in very close into the interior and previously unseen, and also going out millions of light years into the universe. That’s what I’m trying to deal with in my work. I think that the more we flesh out and inquire about our connections with artworks, the better, because we’re fulfilling our ability to desire more knowledge. The older I get, the more I read. I don't know enough. I’ve reached the point where I’ve realised that there’s a finishing post getting closer, so you treasure the time that you have. It's quite important not to waste time, so I try not to.

ZM: How does that sort of awareness come out in your practice?

IF: I start early. If you live in a climate like this, it’s very pragmatic. The early morning is the best part of the day, especially in summer. If I get up at that time I'm in the studio by five o'clock. If I work for five hours, I’ll finish at ten in the morning, which means that I don’t feel guilty when I sit down and read for an hour or two. I just try to pack the hours in.

ZM: What do you usually do in the afternoon?

IF: Listen to music. Read. Make more art. Maybe have a snooze.

ZM: This studio space, and this couch here, is really the best place to have a break.

IF: It is. I can sit and read, I can look at my art, and I can listen to music. It all ties together.

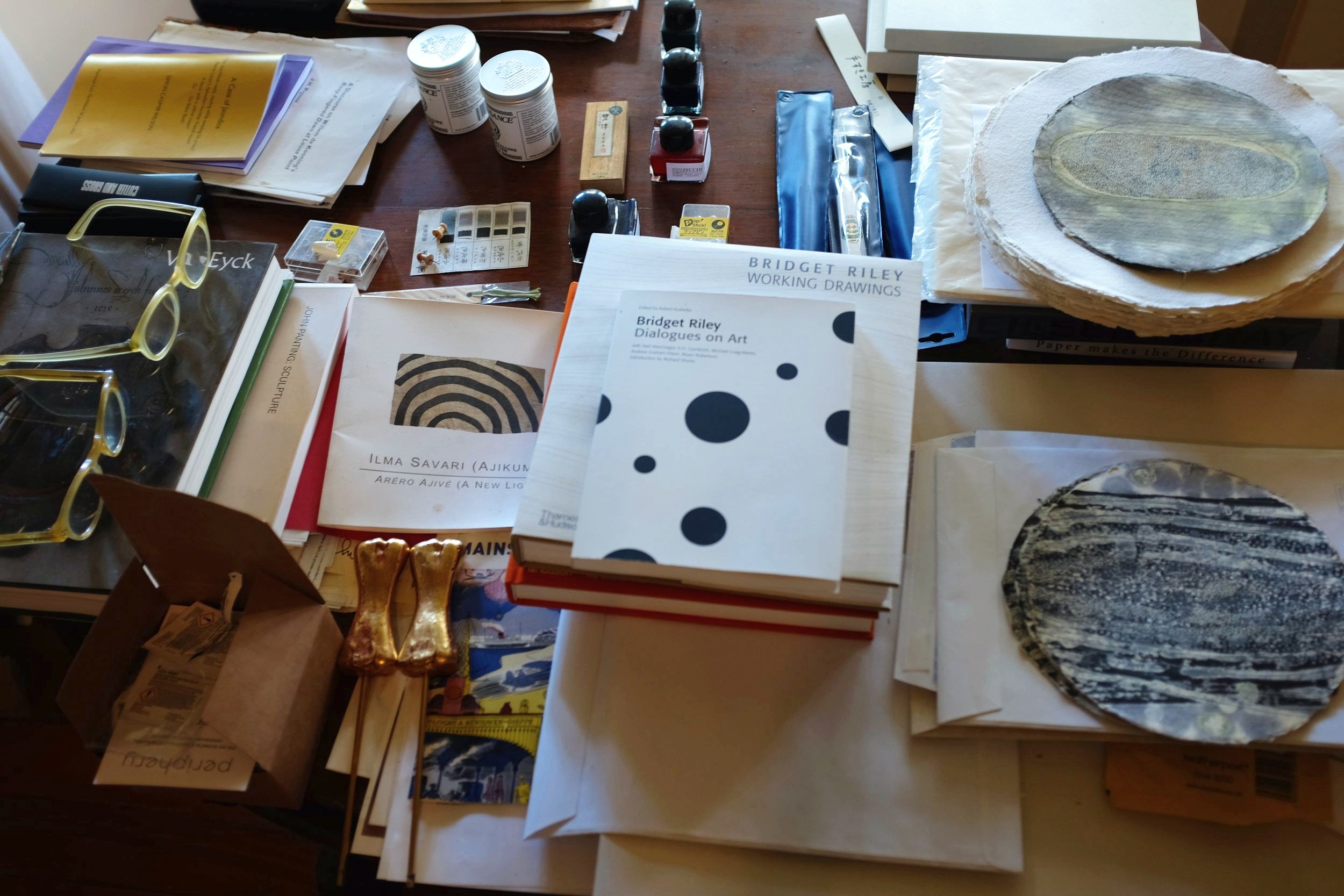

ZM: You have a few sculptures here in your studio. Can you talk about them a bit?

IF: Well, this exhibition is going to have three sculptures, which is new. I trained as a sculptor years ago, but I haven’t made sculptures for a long time. However, things have started to happen recently, and I wanted to see them realised.

ZM: What pulled you back into sculpture?

IF: Actually, a piece of soap that a friend gave me, which these works are modelled from. As I was using this bar of soap, I just gradually formed it into that curved shape. I remember holding it one day and thinking that it looked like a little Cycladic, Minoan, or ancient piece of sculpture, like a little figure. This piece in particular is a projected monument for Francis Ponge, a poet from Montpellier, France, who wrote a prose poem about soap during the Second World War. Soap was so difficult to get during the War that it became much like a precious object. I like to think of this sculpture as a maquette for a monument to Ponge, which I would like to see standing in Montpellier.

There’s also a kind of alchemy about it. I am reading The Experimental Fire by Jennifer Rampling, which is about alchemy in England from 1300 to 1700. Even scientists like Isaac Newton followed alchemy, and believed that base materials could be transformed into gold. So, I had three of these sculptures gold-plated. It’s another transformation from soap, to bronze, and then to gold. There’s a kind of alchemy happening there.

ZM: How do you think these sculptures speak to your paper works? Do you think there’s a conversation happening between them?

IF: Yes, there's some things like this... [referring to some works on paper]. These are works that relate, not specifically, but as a defined object floating in space.

ZM: This oval object that's repeated in your works on paper appears much like the shape of a soap bar. Even the markings around it remind me of soap, of the traces – the waxy residue – that remains behind. Is that an intended repetition of form, or just a coincidence?

IF: It’s pure chance.

ZM: How long have you been creating these sculptures for?

IF: These sculptures haven’t just happened. They’ve sort of sat around for a while. I would say that I’ve been working on them for the last three to five years.

ZM: Were the wood sections of the work always intended to be included, or did they come later in the process?

IF: They came later in the process. Initially I just wanted to cast the soap, which I had sent down to an old friend, Anton Hasell, who has his own foundry. He asked me how many castings I wanted, and I said, “Oh, just a few.” So, he made eight, which is the wrong number, of course, because it’s even. So, I divided it up into five and three. Five are patinated bronze and three are gold-plated. The idea of their bases gradually came into my mind through the process of drawing. I thought it would be nice to actually have that chamfered kind of form, which leads you up and into the actual form, rather than having a rectangular base. A friend who makes furniture, Steve Holna, helped a great deal with the ironbark bases.

ZM: A rectangular base would be very museum-like, wouldn’t it? This pyramidal form by comparison is quite ancient, almost religious.

IF: Yes, it’s more classically Egyptian. I did think at one time of getting one made from marble. I might still do that. But marble is quite monumental, almost funerary.

ZM: Was wood your first choice?

IF: Yes. This ironbark has a kind of warmth. Parts of it have also cracked slightly, and there’s a breathing element to it. I also have a sculpture modelled from a pomegranate, which refers to Persephone, the yellow work on paper. In that work you see the descent into the underworld, and then the generation of spring when Persephone re-emerges.

ZM: Did you intend to create an inversion of the triangular form that exists both in the sculpture and the work on paper?

IF: No, it just works. It’s one of those lovely things that just works by chance.

ZM: I also wanted to return to an earlier comment you made today, that you’ll be including some very large and very small works in your upcoming exhibition. What is it like working with such a variety of sizes?

IF: I find myself working at a different tempo, and with a different kind of focus. I find it quite challenging working in a very fine, intimate kind of method, to then make something quite large. As long as it all works in a complimentary way that’s fine.

ZM: What sort of experience would you prefer that viewers have with your works?

IF: I want viewers to have their own authentic experience with my work. I don’t believe I’m here to be didactic, or to beat any social, cultural, or political drum. I'm just here to offer up my views of what it's like to be alive, to be in the world, and to respond to nature and life in a very tangential kind of way.

I've been spending a lot of time reading about women artists too, how some have prevailed and others have struggled, especially if they're partnered with a male artist. I think Bridget Riley and Barbara Hepworth are probably the two great female artists of the 20th century. The other thing is that I love having other people's work around me in the studio. I like to bounce off other works. We collect art as well. Not only to support younger artists, but also just because we love having our own collection. I was pleasantly surprised when I realised that most of the work in my studio, other than mine, was by women artists.

Ian Friend’s exhibition The Days Run Away is on show at Jan Manton Gallery from 19 January - 6 February, 2022.

Interview by Zali Matthews. Edited by Zali Matthews and Embie Tan Aren. Photography by Embie Tan Aren. From the Studio content courtesy of Jan Manton Gallery and Ian Friend.