From the Studio - Interview with Natalie Lavelle | 17.02.22

In the lead up to Natalie Lavelle’s upcoming exhibition Ways of Being, the JMG team took a tour around Natalie’s studio to peek at recent works and chat all things painting, process and beyond. Natalie’s recent work shifts its gaze to the natural world by evoking both curiosity and nostalgia in layers, bleeds and sweeps of white, brown and blue. Each work expands beyond the canvas to suggest a vista of colour, light and material — seemingly both contained and spacious.

In this interview, Natalie joins Gallery Manager Taylor Hall and Gallery Communications Embie Tan Aren in conversation about her practice and the imprints of landscape, art history and spontaneity of process that have motivated it…

Taylor Hall (TH): Nat— I wanted to start off by noting that your last series Rekindle (2021) seemed to lull in the ether —with its soft shimmers and pastel colours, whereas these works are a lot more grounded.

Natalie Lavelle (NL): These new works embody weight and seem to be grounded in themselves. There is also an essence of the world around us within them — that's why I have been intrigued by this idea of vast and expanding fields and vistas. Most commonly, a vista is a sweeping landscape. However, it can also mean looking towards a future. The vista becomes present in many of these works by the semi-exposed linen edges. It's like you're looking at and looking through something at the same time onto this vista of colour, or maybe backwards in time to other art periods in history, specifically Colour Field painting or Korean Monochrome painting. I have been thinking of Helen Frankenthaler; a lot of her paintings are reminiscent of the landscape and her soak-staining symbolizes landscaping.

Embie Tan Aren (ETA): I like how you mention ‘staining’ not only in Helen’s work but as an act that is part of the landscape, because the landscape is kind of imprinted onto a lot of what we do.

NL: I like the idea of imprinting a thought, memory, or just a moment with nature.

ETA: Landscapes are ingrained in us, even if we don't really think of them. They’re always present in that way. And staining solidifies how they’re involved in your practice, whether implied or not.

NL: I love how you mentioned that. I was talking to Louise Mayhew (essay catalogue writer) about how both the landscape and viewing an artwork have a plethora of possibilities. But, essentially, our perceptions are deeply grounded in what we know; history, knowledge and philosophies of painting that determine how we read what we see. And when the artist’s practice aligns with what the viewer sees, it works. That's what I'm trying to conjure.

TH: It's the remembered landscape, but not in a visual sense. Your work asks: what elements do you carry with you when you've experienced the landscape? It's not necessarily always pictorial. It could involve hazy memories and colours.

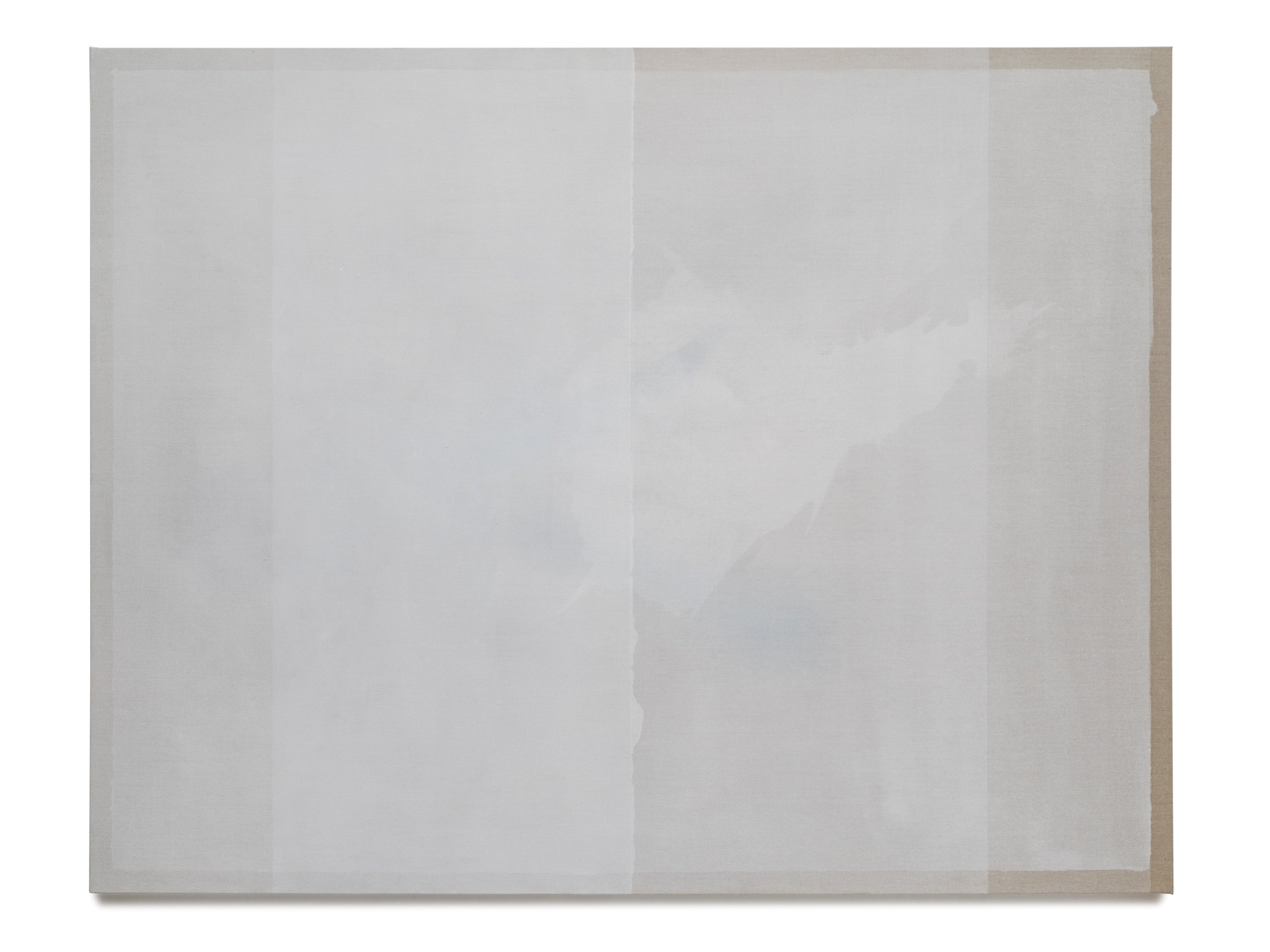

NL: Yes, it’s the essence of something felt - it’s pre-language, like some of Elizabeth Newman’s work. One of the works included in this exhibition is called Wordlessness (a sense of the present). It is made with the thin, washy oils – you can see how they have gently soaked into the raw linen. The title indicates a state of being in the present that you perhaps don't have words for just yet.

TH: To me it looks like a wispy sky or ocean.

NL: All of these works are much like fragments of something bigger than themselves. There are a few works that have been framed using woods that have been matched to the painting itself – each one keeping the content and energy of the work contained. The unframed paintings seem to almost slip off the canvas to become part of the space around them.

ETA: This one reminds me of how memories can leave that ‘visual stamp’. When you look at a landscape, you may not remember every detail of it or the whole experience, but it leaves a stamp of what that moment was like. It’s expansive both in the present and in your memory later on. It just kind of sticks.

NL: Yes, it’s that act of imprinting you mentioned earlier. It's not the bigger picture. However, it has the capacity to immerse you in something more.

Artwork: Wordlessness (a sense of the present), 2022, oil on Italian linen, 105 x 155 x 2cm. Image: Louis Lim.

TH: Especially with the scale of some of your work. They’re almost human-sized and all-encompassing.

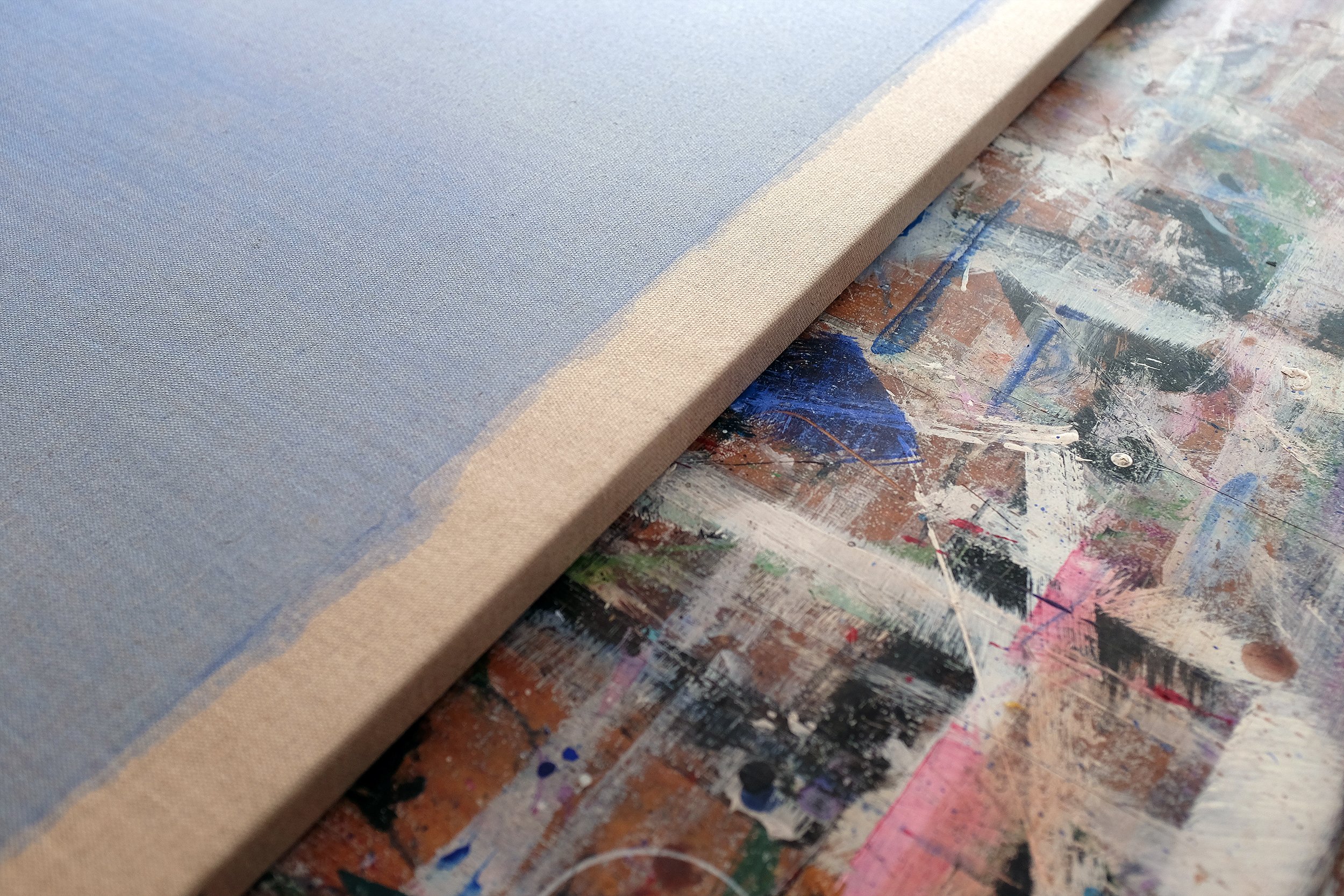

NL: Most of them are large, landscape orientated works. I have recently felt more aware of a painting being a moment in time. Each work with its entry point, body and exit point – something that can be perceived as you walk past. The method of applying paint onto a canvas laid flat on the ground, allows the paint to seep, soak and stain the material and gives in to gravitational pull. I think this is what gives these works that weight, embodying the residue of any gestures created on the surface. For example, the bleeds are a significant part of my work. The word ‘bleed’ has so many connotations, which I just love. I think keeping my own input on a par with the material agencies has become a default now.

TH: There’s such a freedom to that.

NL: And I like that they're not so constrained.

TH: Not so defined.

ETA: Not defined, not structured. It’s allowing that bleed to come through and have a release.

NL: The bleeds to me are soft and feathery.

TH: It invites you in with colour. It's not foreign—it's very familiar. Your work is not only reminiscent of the memorability of landscape, but also its expansiveness. There is an endlessness to something that in essence may seem simple but contains so much complexity. You’re very elemental in the way you work, which gains you that expansiveness.

NL: Rekindle (2021) delved a lot more into overlooked periods of art history, but I think this series has become a little bit more personal. Even the titles I've given them have a kind of personality, for example, A Moment of Closeness and The Nearness of You. I still very much relate these works to the body, a construction of the abstract and the physical. It’s nature of being a painting, is what I’m trying to present.

TH: Can you tell us about the sculptural piece included in the show?

NL: Yes, I’m excited to have The Nearness of You standing in the gallery space. A fabricated steel framed with a power-coat finish has been custom built to house this work. The frame itself is proportioned to the size of my own body. The painting starts at my hip height and the stand at the bottom has taken my leg length and feet measurements. Even when I paint, my brushes are the width of my hand. When installed in the gallery you'll be able to walk around the structure. You are invited to see the red cedar stretcher bars and frayed linen on the verso. I so enjoy stretching my own supports. I consider it to be important to my process.

TH: It’s an act of care as well.

NL: Yes. I'm making this new body of work from scratch. Each work is stretched on a beautiful red cedar frame. When they’re all together in a room, you can smell the cedar essence.

TH: You’re really emphasizing those natural elements and the organic qualities of the materials you’re working with as well as eliciting the landscape as an inspiration for this series— how did you consider the precedence and expectations of landscape painting?

NL: I considered this idea of the natural world. I don't know yet what that means for my practice, but it's always been considered and I'm trying to relate more to the genre of painting. Painting has its own history, knowledge and connection to the landscape.

I'm thinking of calling the show Ways of Being in reference to ‘Ways of Seeing’ by John Berger, because the works are as much about perspective as they are about existing in that natural state of being a painting. I think that's more the crux of the show, this nature of being a painting. I have always been interested in the ontological nature of a painting or, it’s state of being and there is one theorist, Barry Schwabsky, who says that knowledge and philosophy is construct to reference a painting’s ontology. I think it's important to represent a painting in its most essential state. I am interested in finding other points of historical reference away from Western minimalism and towards Eastern philosophies.

TH: Yeah—Minimalists such as Anish Kapoor and Jeff Koons create these shiny, perfect objects that are so distant from the body. Their flawlessness doesn’t evoke the spontaneous flaws and faults of the human, but rather erases them. By comparison, your Minimalism, as well as general Post-Minimalist tendencies, lean into the sensibilities of the characteristics of the medium and the materials.

NL: That is absolutely considered in this body of work. And that is definitely where this body of work is going. As with what you're saying, maybe it’s not a full picture of a landscape, but something you might remember from it. Like an imprint. But it’s still very real.

ETA: It doesn’t make it any less of an experience. It still has that value of being a holistic experience for you.

NL: I think that I have thought a lot through the physical painting process — a lot is worked out on the canvas rather than being premeditated. If I have a smaller bleed, or a big bleed, I might go, “I like that, I’ll do something to make that stand out or do something else next”. My next move is dependent on my current move. It’s a process for me.

TH: There’s an unexpectedness to it.

NL: Yeah, exactly. And it depends on timing as well, such as if I’m working on a hot day, or if I’m using acrylics or oils. I pour on the paint and it might seep into something quickly to create an imprint. Then as I’m painting through, I work with different areas that dry at different rates.

ETA: It’s kind of moving in its own way—it doesn’t wait for you. It’s like its own entity.

NL: Yes. It is its own entity. Looking a little at Eastern philosophies and reading about those ideas, I think that perhaps elements of nature and the natural world could be a boundless way to think about painting.

ETA: I feel like we always have an affinity to the landscape. No matter what you do, the environment is important. We exist in nature, so it makes sense that the landscape is always going to be involved in art.

NL: I’ve always been concerned with the nature of a painting — being itself, its own body, with a front and back, face and body. But if it is a painting, it's also part of the greater world. Nevertheless, these paintings have a personality—I often think about them as portraits of colour, or portraits of a painting.

TH: You seem to decentralise the hierarchy of the human in painting, or the human in the landscape, by creating a level playing field.

NL: Yes. I think that all started with the agency incorporated within the work itself, and within the materials.

TH: This emphasis on the environment and landscape is very apt. Not that your work discusses political topics such as climate change, but I think we’re very aware of our surroundings and what is topical.

NL: I feel like we are very aware of the environment around us, especially amongst young adults today. That’s a real thing that we’re thinking about: how do we make it better for our future, and the future of the next generations?

ETA: Maybe it’s just me: I don’t know whether it’s an illusion, but when you put those segmenting lines and shapes in your works, it makes the painting look larger.

NL: Yes. If I were to paint the edges, it would look contained. It’s almost like the painting is going to burst because there’s so much confined energy there. By leaving segments of canvas untouched, it allows for some relief and an expanse in the field.

In this show, even if it’s just with browns and blues, I keep coming back to Colour Field painting, because they allowed this expanse of colour and paint to happen. They didn’t have to keep it in energetic bundles (like Abstract Expressionism) on the canvas anymore.

TH: It affords you more time with basic elements. It’s insane how a colour, shape, bleed or form can resonate so deeply. You don’t over-complicate things. [Gestures to Wordlessness (a sense of the present)] this is the sky to me. I didn’t realise that something so all-encompassing and intrinsic to my reality could be depicted with one washy colour that has been very thoughtfully applied.

NL: It’s more alive than it is still. It’s not on the surface. I think it transgresses the idea of physical and pictorial space. Essentially, I think painting was made to be pictorial space only: “This is what we’re looking at here,” or, “This is what we’re imagining”. I like to think that what I’m trying to do is expand and push painting at its fundamental stages to see if I can keep investigating this field.

TH: Where do you stop?

NL: I don’t know!

TH: Your work has this idea of the body. You do this thing with your exhibitions in which particular works act as a precursor to the next. You’ve got one artwork that challenges the rest, but just enough that the body of work remains. For me that work is The nearness of you.

NL: Yes, it’s trying to relate back to both the abstract and the physical, which is what painting is. That’s what I like about it: it is based on that theory.

TH: With regards to Minimalism, it not only the distance from the human, but academically speaking, from the general public. There’s a certain gatekeeping going on in minimalism— a lot of its meaning is hidden in convoluted academia and reserved only for the ‘eloquent and educated’.

ETA: Like a hierarchy. Only a certain group of people could be a part of it or enjoy it.

NL: I agree with what you’re saying. I once read something that said, “Literalist art is only for the artist inclined, because others don’t understand it.” But that’s not true.

TH: Alternatively, you allow viewers to intuitively respond to your works. The meaning of the work is determined as much by the viewer as by the work itself.

NL: Yes, exactly. I can step away, because this painting is what it is. I’m not saying it’s anything other than a painting, it’s just what you perceive it to be. You’re the viewer, and that’s your role. I painted it, but ideally, if my concept is my project, and the viewer can gauge it as a painting, then I’ve achieved something. Because it’s all about connection. So that’s what I look towards: I don’t have to come up with something, I just have to try to present a painting as itself. That’s my goal.

ETA: Yeah. That’s your agency as an artist. What you create is within your control, but you don’t tell other people how to perceive it. I feel like as a female artist, you may feel like you have to over-explain or tell people, “This is what I meant by this..” or “It’s about this..” But for you, it’s like: “I’ve just made this painting and it’s your role to perceive it how you want to.”

TH: It’s a rejection of the “genius artist” in favour of: “I’m a human, and you’re a human.”

NL: Yes, we’re all in this together.

Natalie Lavelle’s exhibition Ways of Being is on show at Jan Manton Gallery from 9 - 27 March, 2022.

Interview by Taylor Hall & Embie Tan Aren. Edited by Zali Matthews, Taylor Hall and Embie Tan Aren. Studio photography by Embie Tan Aren. Artwork photography by Louis Lim. From the Studio content courtesy of Jan Manton Gallery and Natalie Lavelle.