From The Studio— Interview with Joachim Froese | 02.09.2021

Jan Manton Gallery visited Joachim Froese’s studio in the lead up to his upcoming solo exhibition Echoes of Process, September 15 - October 3, 2021. Froese took us through each step of his detailed & precise salt-printing process used to create works included in the exhibition and discussed with us the significance of merging old and new photographic processes and beyond.

We sat down with Joachim to find out more…

You have been developing your photographic processes for almost 40 years now but using the salt printing technique is quite new for you! Can you talk us through your incentives to master this technique?

When I went to art school from 1992-96 the world was still analogue, and we used film and worked in the darkroom. At the time I only worked in black/white, enjoyed the craft of it, and strived for some mastery in this area. However, when the digital change came a few years later, I adapted easily. Before my migration to Australia, I had worked in the graphic industry in Germany which meant I was familiar with the first image manipulations systems that appeared in the late 1980s. In the early 2000s I embraced digital photography as it allowed me to finally work in colour the way I wanted to.

With Echoes of Process, I am returning to analogue black/white photography but this time it means a completely new mode of working as most of the beautiful black/white papers and developers I used before 2000 aren’t around anymore – at least not in Australia. I now make everything myself from scratch and I am returning right to the beginnings of photography. Salt prints and cyanotypes are handmade: a sheet of paper is coated with one or more chemical solutions which I mix up to create a light sensitive emulsion. My darkroom has transformed into a small chemistry lab.

When I began to work in this manner, I simultaneously started to read up on the processes I use. I became interested in the beginnings of photography, and how it emerged during the first half of the 19th Century. Reading about Henry Fox Talbot and the other pioneers of photography went hand in hand with using their processes.

Another incentive to look at salt printing was a project that I still had in the draw: photographs of seedlings, which I began to raise in 2014 as part of a PhD I undertook at RMIT in Melbourne. Back then my thesis looked at human categorizations of nature and as part of my practical component I used these images to develop large outdoor displays, commissioned in Brisbane and the Spreewald near Berlin. I had been happy enough with these installs but still felt that I hadn’t found the right format for my imagery.

Eventually, after finishing my PhD in 2017, I started to work on my seedlings again, this time as salt prints. Then I found out about Talbot’s interest in botany and many other interesting connections between the beginnings of photography and botany. This is practical research: you start playing with a process, you read about its history, you refine the use of it, you read more about the artists that used it, ideas grow, a concept develops – and before you know it a body of work starts to happen and take shape.

Dichanthium sericeum, 2021, From the series Entangled, Salt print, 20 x 25 cm.

Edition of 6 multiples: 2/6 (+ 2 AP).

Some of the processes are very tedious and time-consuming, as someone who has also experimented widely with quick-paced digital mediums, how does this slow, almost meditative process sit with you as an artist? What has it birthed?

The exposure for the earliest surviving camera photograph, Nicéphore Niépce’s View from the Window at Le Gras taken in 1826, lasted approximately 8 hours. It is estimated that in 2017, within the same time frame, around 1 billion photos were taken worldwide (equating to approximately 1.3 trillion a year). Every two minutes, humans now take more photographs than were taken during the entire 19th century. This almost incomprehensible avalanche of images is directly linked to the smartphones we use, interlinked with social media platforms. Photography has become instant. Once taken, within seconds a photograph can be viewed around the world. Photography has eliminated time and distance. We take photos without much thinking; they have infiltrated into our lives to a point where we don’t’ notice them anymore. It’s become like breathing, we do it without feeling each breath.

But there is a backlash. The background of omnipresent fast photography now leads to the re-evaluation and appreciation of historic, analogue processes, they are perceived as different, they start to merge with printmaking. It makes sense, they use similar workspaces and materials: wet areas, UV exposure, art papers and chemicals.

Historic processes slow things down and in your question, you mention meditation. Again look at breathing. Breathing exercises constitute some of the most basic meditation techniques: you become aware of something you do all the time; you value every breath you take. Washing, toning, and fixing a print for more than an hour can become quite meditative as well. You keep rocking a tray in the darkroom, again and again and again. You start to notice photography again, at the end of this process you value every print that has worked out.

Coupled with the precision of your printing process is the care you have taken with the inception of the photograph (hand rearing the seedings, i.e the subject matter) as well as the finalised artwork (building and staining the frames). It seems you have really focused on creating a holistic body of work as a lot of attention has been paid. Why is this?

My exhibition is titled ‘Echoes of Process’. Process lies at the heart of all artistic practice but in this exhibition the echoes of process run as a common thread through the entire show: From salt printing to toning cyanotypes and staining my frames, from the birth of a plant to the death of a tree, my work collapses the distinctions between the processes it uses and describes.

Seen from such an angle this is probably the most holistic work I have ever made, I even decided to build my own frames. I wanted to make everything myself, from start to finish – in fact it starts with the cultivation of seedlings well before I even take the first photo. As distinct as all the stages seem to be, gardening, framing, and printing, there are remarkable overlaps in the processes I use. Plants and photography both rely on photochemical reactions, I use organic matter as my subject matter and my medium, I use similar chemicals for toning cyanotypes and staining my frames, and I finish my final prints and frames with wax and varnish.

All this is the result of playing with process. The more I delve into historic photographic processes, the more I get sucked in by the alchemy they evoke. Some of the photochemistry I use is in fact rather basic and I use many common ingredients such as salt, vinegar and tea. It is huge fun when it works, but it also tests my patience. As described earlier, using self-made chemistry and organic materials introduces significant, and sometimes frustrating inconsistencies into my workflow.

We are very excited to present your exhibition to our audience. What do you hope people take away from the show?

That’s a very broad question… An artwork can only succeed as an interactive experience. At the moment when a viewer looks at my images, their world and my world begin to overlap. The thoughts and feelings the viewer brings to the gallery meet the thoughts and feelings I put into the work. For me, this almost magical overlap is the essence of art. Some of it is controllable, some of it is not. I guess, it’s yet another complex organic process.

I want my photographs to work visually, I am trying to create a kind of beauty. If viewers appreciate that and engage little further, be my guest. However, if they feel there is more to the work – and I hope they do – then there are a few anchors that allow them to engage with the processes and concepts I use. I am not making political art in the sense that I am telling the viewers what to think. I want to make them think for themselves – about processes and how they are connected, about what photography might be for them and about how their life and actions might be connected within the wider system that makes our planet a living planet. This interview is a great way to introduce the viewer to some of the ideas and concepts that underpin this exhibition, thanks for making it possible!

You embrace the development of digital as well as analogue photography and it is fascinating how you have combined the two in your current work. You must be elastic and open to celebrating the history of photography as well as embracing the future of the medium. Why is it important for you to bridge both the past and the present in your work?

When we talk about photography, we often forget that the term covers a broad range of very different technical processes, all of which offer distinct formal and conceptual frameworks. Since its inception photography has gone through staggering technical changes and new inventions have continuously re-defined the medium and its use: the carte de visit in the 1860s, the roll film and the box brownie at the end of the 19th Century, the Leica camera and the industrial printing press in the 1920s, colour photography in the 1960s, digital image capture since 2000, and most recently social media platforms. All these new technologies changed the parameters of photography in fundamental ways, they changed what could be done with photography and the way it was used. Even in my lifetime the practice of photography transformed dramatically. I am interested in these changes as a practicing artist and as a scholar.

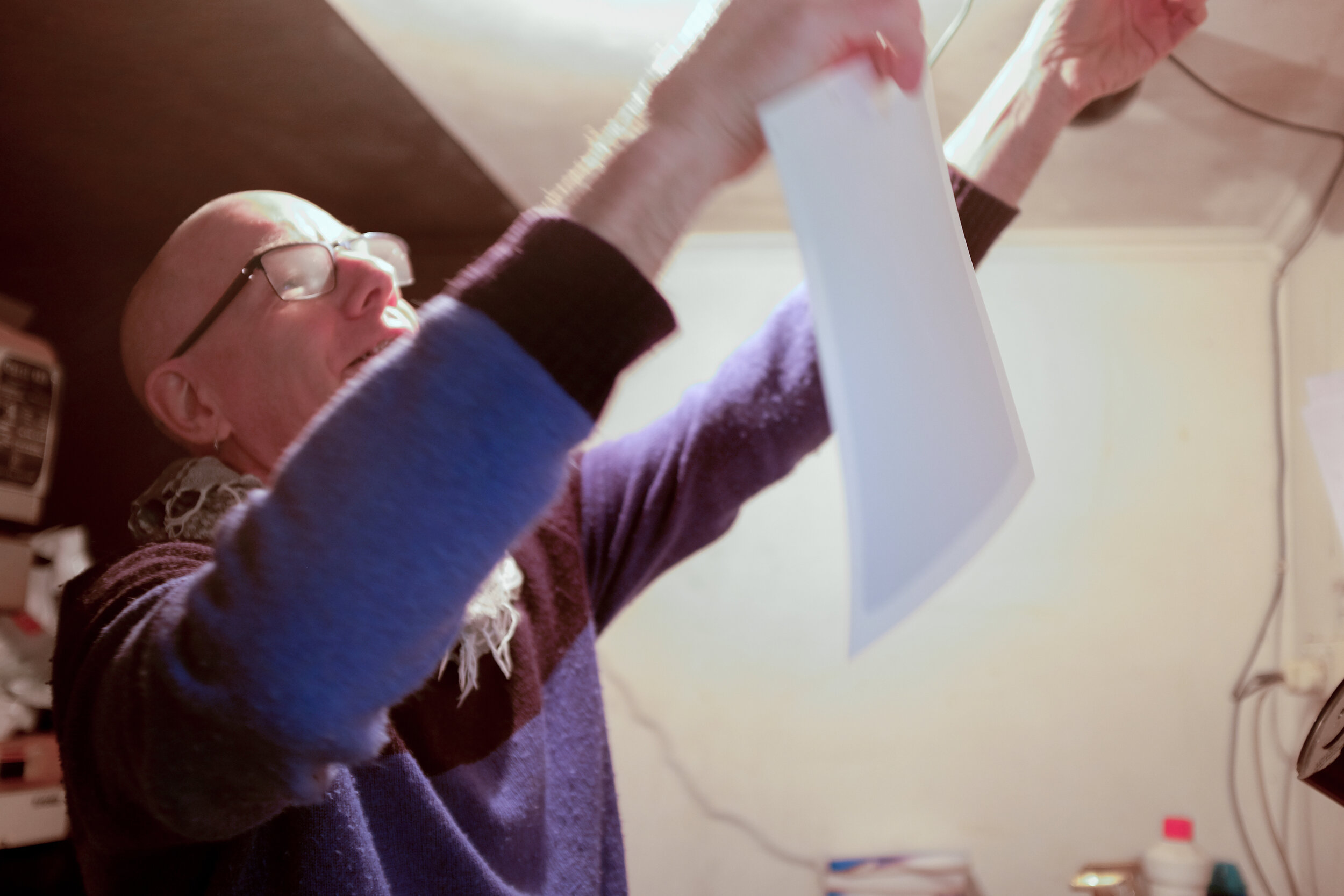

My current work is based on a hybrid process that includes two distinct stages in which I use distinct technologies: digital capture and analogue printing. I use a digital camera to take my images and I manipulate them in Photoshop. I usually combine several exposures to maximise focus and blend lighting set-ups. I then convert my files into a black/white negative image, which I print as an inkjet on transparent film. Up to this point, the workflow on my computer is predictable and repeatable, the digital parameters I work in are completely stable and I can work fast.

The next phase – salt printing – is a whole new ball game. Now I am working analogue and I use one of the oldest, most fickle, and frustrating printing processes in photography. Chance, as much as I try to eliminate it, begins to play a role. Every time I make a print, the analogue parameters change slightly, now they are not entirely stable anymore. Salt prints, more than any other process, react to even minute changes in temperature, atmosphere, and chemistry. Every print turns out slightly different. I have spots, the print is too light or too dark, contrast and density change, the tone of the print changes. To make a single print takes me the best of a day and at the end of it many are thrown out. Working in this hybrid manner means working in two completely different headspaces.

The final salt prints I arrive at are hybrids as well. They look different compared to their historic counterparts, they are much sharper, for example. Similarly, the digital files I initially took don’t look digital anymore either, as they have lost a lot of sharpness. All my prints vary in tone and have different coating marks, they are multiples rather than exact editioned copies. The prints I hold in my hands at the end of the day are bridging the past and present of photography.

You not only use historic printing processes, but you also engage with early concepts that emerged through the use photography at the time. During our visit you talked about, how the media was perceived back then and how it blurred the line between art and science. Can you talk a little more about this?

When several photographic processes were announced in 1839, people weren’t entirely sure what this new thing was. Henry Fox Talbot, one of the ‘inventors’ of paper photography and the salt print called his first images ‘photogenic drawings’. In 1844 he published a book titled ‘The Pencil of Nature’. He stated that through his process nature was able to ‘reveal itself’. From our perspective today we would probably describe Talbot as a scientist.

On the other hand, in France, paper photography became popular amongst artists; Hippolyte Bayard, one of my heroes, was one of them. Others, like Gustave Le Gray and Henri Le Seq were students of the painter Paul Delaroche. Today we might describe these guys as nerds who went out to explore the artistic potential of an exciting new technology. It is important to remember that there were no textbooks around that explained the process, it was all very experimental. Right from the start photography excited scientists and artist alike, the new medium and its emerging practice sat right between nature and culture.

What interests me particularly in this context is that Talbot also was a keen and very knowledgeable botanist. For his first photographic experiments he used herbarium specimens, flat pressed plant material he put straight onto his light sensitive paper – the earliest photograms. Initially he saw his invention as an aid to catalogue botany samples and early on he sent some of his photograms to recognized botanists around Europe to get them interested in his process. He also had an ongoing and fruitful correspondence with John Herschel, another important photography pioneer, in which both regularly exchanged specimens of photographic prints and flowers. There are numerous other connections that can be drawn from botany and horticulture to the beginnings of photography, all of which continue to inspire my work.

During our studio visit it became obvious how sensitive your organic printing processes are, and how you need to maintain a careful balance (percentage of chemical substances, careful washing of surfaces and paper, ensuring the purity of process) within every step. You also mentioned that the birth of each seedling highlights the most vulnerable stage of its life. Does this organic precariousness act as a metaphor in the works for the urgency of environmental balance at large?

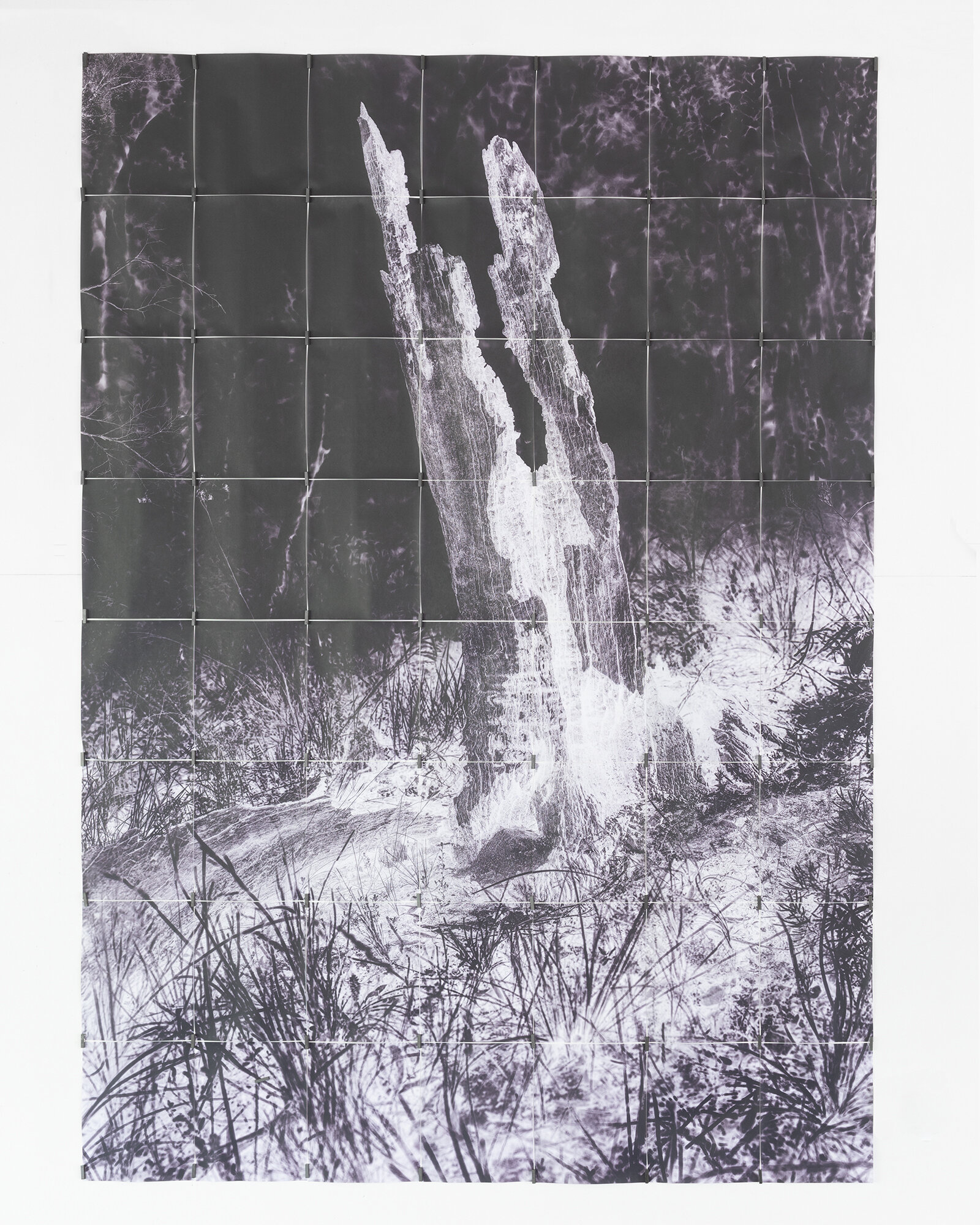

Very much so. I truly believe that we as humans need to understand that we are part of a highly complex and precariously balanced ecological system. In this exhibition the salt printed seedlings are shown next to a large panelled image made up of 56 tea toned, black cyanotypes, depicting a burned tree stump. I made this image using waxed paper negatives (which are also on show) during a recent residency at BigCI, located at the edge of the Wollemi National Park near Bilpin. The image acts as a reminder of the devastating bush fires which, fanned by global warming, devastated the Blue Mountains almost two years ago. This is yet another processes I describe: first and foremost, the life of a plant from birth to death. But I hint at further processes that influence this biological cycle: climate change, induced and fanned by humans. My seedlings break out of dark soil into a black void, their future is unstable.

We live in a consumer society that is obsessed with consumer items but pays little attention to the mostly hidden processes required to generate them. Yet all our modes of production have consequences far beyond the things we crave so much: they use resources and energy, and they produce waste. These are by-products of the interconnected and entangled processes we use. Messing around with complex systems, and unwanted outcomes.

Working with organic processes such as salt prints and cyanotypes has taught me a lot about complexity. Tiny changes to the chemicals I use, or small contaminations immediately change my prints. All biological life on our planet is ultimately based on processes like the ones I use in the darkroom. Earlier I talked about the different parameters of digital and analogue workflow. I guess they stand exemplary for a much broader conundrum we face as a species. Our technological advances and competence delude us into thinking that everything we do is predictable and that we can separate our fate from the organic, far less stable parameters which our existence is embedded into. We share this planet with a non-human world around us, interconnected within an environment that is less controllable than we might think.

Joachim Froese’s exhibition Echoes of Process is showing at Jan Manton Gallery from September 15 - October 3, 2021

Interview conducted by Taylor Hall and Embie Tan Aren, Edited by Zali Matthews. Images by Embie Tan Aren. From the Studio content courtesy of Jan Manton Gallery and Joachim Froese.